Note from the Playwright

I was nine years old on April 20th, 1999, the day that Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold carried out their plans to “go NBK” and bring death and destruction to their Littleton, Colorado high school. It was a watershed moment for anyone my age who spent their time inside an American school which was now, even in a staid suburb like Littleton, a potential shooting range. This is what has been so scarring for the Popular American Consciousness: White Flight into Suburbia was supposed to mitigate exposure to the violence of The City. And if children aren't safe in suburban school, the one place parents are forced to leave them without supervision, can they be safe anywhere? Dylan and Eric terrified children and adults alike because we recognized in them people that we all knew to be around us. Though many would be too ashamed to admit it, even as a nine year old I knew that the weird kid in the corner was no longer just quiet-these people were suspect and given a wider berth, socially, for fear of what they would do.

I responded by writing a poem. It was set in one of Columbine's classrooms, told from the perspective of a student hiding under his or her desk. Though I'm sure the poem is lost in a pile of old notebooks somewhere, I cannot find it. I do, however, recall the student reflecting on the screams of victims in other rooms echoing down the halls, and that the poem ends with the question, “When will my scream come?”

The Columbine shooting was a remarkable event in that the local television crews were on the scene before the SWAT teams. It was on every station, and America helplessly watched it happen. As cameras stayed fixed on the school's windows, the nation learned about what was going on inside from the rumors that escaped students were repeating in interviews: boys from a group called the Trenchcoat Mafia were taking cues from the Marilyn Manson songs they listened to and targeting jocks, Christians, and persons of color in a planned shooting. Of course, none of this is true. Eric and Dylan were not part of the “Trenchcoat Mafia;” that group of friends had graduated before them. They hated Marilyn Manson, and preferred bands like KMFDM (I feel confident saying that Eric and Dylan would have labeled Marilyn Manson, predictably and moronically, as “gay”). It wasn't a shooting; it was a failed bombing that devolved when their fuses wouldn't go off. And as frightening as it is, Eric and Dylan weren't targeting anyone in particular. They just wanted to kill as many people as possible, hoping to beat Timothy McVeigh's contemporary record for the deadliest attack in American history. In fact, Eric and Dylan were well aware that what they planned to do was “bad” (after all, they thought of themselves as “bad,” too). The more I researched them, the more I learned that the popular conception of the two boys was largely inaccurate.

I started researching Columbine after the Sandy Hook Shooting in December 2012. Like just about everyone, I had a shocked reaction to the horror of Newtown, but was disappointed when I began hearing the rhetoric surrounding the perpetrator, Adam Lanza. Whether it was commentary from news pundits or people I know personally, the way we talked about Adam took me back to Eric and Dylan: these were “monsters” and “no one could understand how they could do something like this.” In a word, they were “inhuman.” This assessment is willfully ignorant. It stems from a mind too afraid to admit how close (both figuratively and literally, because these are people who could be our neighbors, or worse, our own children) we are to these people, and how incredibly “human” their behavior actually is. Open a history book if that claim is doubted. Man's inhumanity towards man is very human.

“I think right now our most important teachers must be Russell Henderson and Aaron McKinley. They have to be our teachers. How did you learn? What did we as a society do to teach you that? See, I don't know if many people will let them be their teachers. I think it would be wonderful if the judge said: 'In addition to your sentence, you must tell your story.'”

-Father Roger Schmit on Matthew Shepard's killers, The Laramie Project

We do ourselves, our children, and disturbed individuals like Adam, Eric, and Dylan, a horrible disservice when we speak of them in that dismissive way. There is something about the Young American Male and the culture that surrounds him that has led boy after boy, ever since Eric and Dylan, to the same conclusion of what they have to do to deal with the pain of living their lives. There is some mistake we keep making, some lesson that we teach but fail to see the message of, some opportunity to help them that we keep shirking from. And in no way will we ever prevent another Sandy Hook or Columbine by distancing ourselves from those who would perpetrate it and refusing, out of fear, to understand them. This does not mean we have to forgive them. This does not mean we have to empathize with them. But with these kinds of mass killings becoming somewhat of an epidemic, to refuse to understand their causes would be akin to refusing to research a cure for a deadly disease, shaking our heads, and hoping we don't get sick. Make no mistake-the cure lies somewhere in the minds of boys like Eric and Dylan. We have to open our ears to them: to hear them when before we ignored them, to make them speak when in life they were silent.

Luckily for me, Eric and Dylan wanted that. They left volumes of material to be found, much of it lying out for the police to find along with their taped confession. Through the released FBI report (containing diary entries, homework with teacher's feedback, AOL chat room conversations, and more) and pirated home videos online, I was able to find what it was that they were trying to express but failed doing (though the massacre was an act of self-expression, I find its violence to constitute an inherent failure). And when it came time to write about the play itself, I realized I could do no better than editing the words they wrote and largely kept to themselves, and filling in the external lives that in affect sublimated all those feelings.

I found the play’s title in Eric’s planner: a reminder to memorize the lyrics of the Goethe poem, Der Erlkönig. The poem, later turned into the Schubert song that Eric and Dylan perform in this play, tells a story about a small child seeing the coming of the titular character, an evil spirit, who ultimately kills the child as the father dismisses the danger. It bore a striking resemblance not only to how people like Dylan and Eric are treated until it is too late, as well as to how I envisioned the boys’ idealized view of themselves: powerful, deadly, takers of children. I think they were largely wrong about this. I see a lot of weakness in their actions.

I hate Eric and Dylan sometimes. Especially Eric, whose searing anger towards all people besides himself and a couple friends disgusts me. I am so mad at them for what they did. I want to smack them. I want to tell them to wait until after high school: go to college or just move out of your parents' house. Extract yourself from everything that pisses you off, this world is a big place. I want to tell them to shut up, that their problems are not actually that big, and to have a little dignity and respect for others. I want to scream at them, and point out all the flaws in their plans, their half-hearted delusions that they might get away, and the fact that they actually were perfectly smart and had interests that could have provided fulfilling lives. And sometimes I want to run away from them. I want to forget all the pain I read in these boys' messy teenage handwriting. I want to forget that they were obsessed by love, especially Dylan; were so desperate to both give it and receive it, but are only known for hate. I want to forget how they, especially Eric, wanted to annihilate our entire species. And I want to forget that any man, like me, could be so wrathful that he could shut off that voice that begs him not to murder passionlessly. But in both those moments, I know that I am wrong. Because if I am angry or disengaged, I could never help them change. I know that I am falling into the same trap of wanting to distance myself, of wanting to deny them, of want to turn my head and avoiding seeing the familiar gleam in the eye staring back at me from their yearbook photos. What they needed was to be reached. They were too afraid to do it themselves; others were likely too afraid or self-interested to take a step towards them. But I hope that The Erlkings comes close.

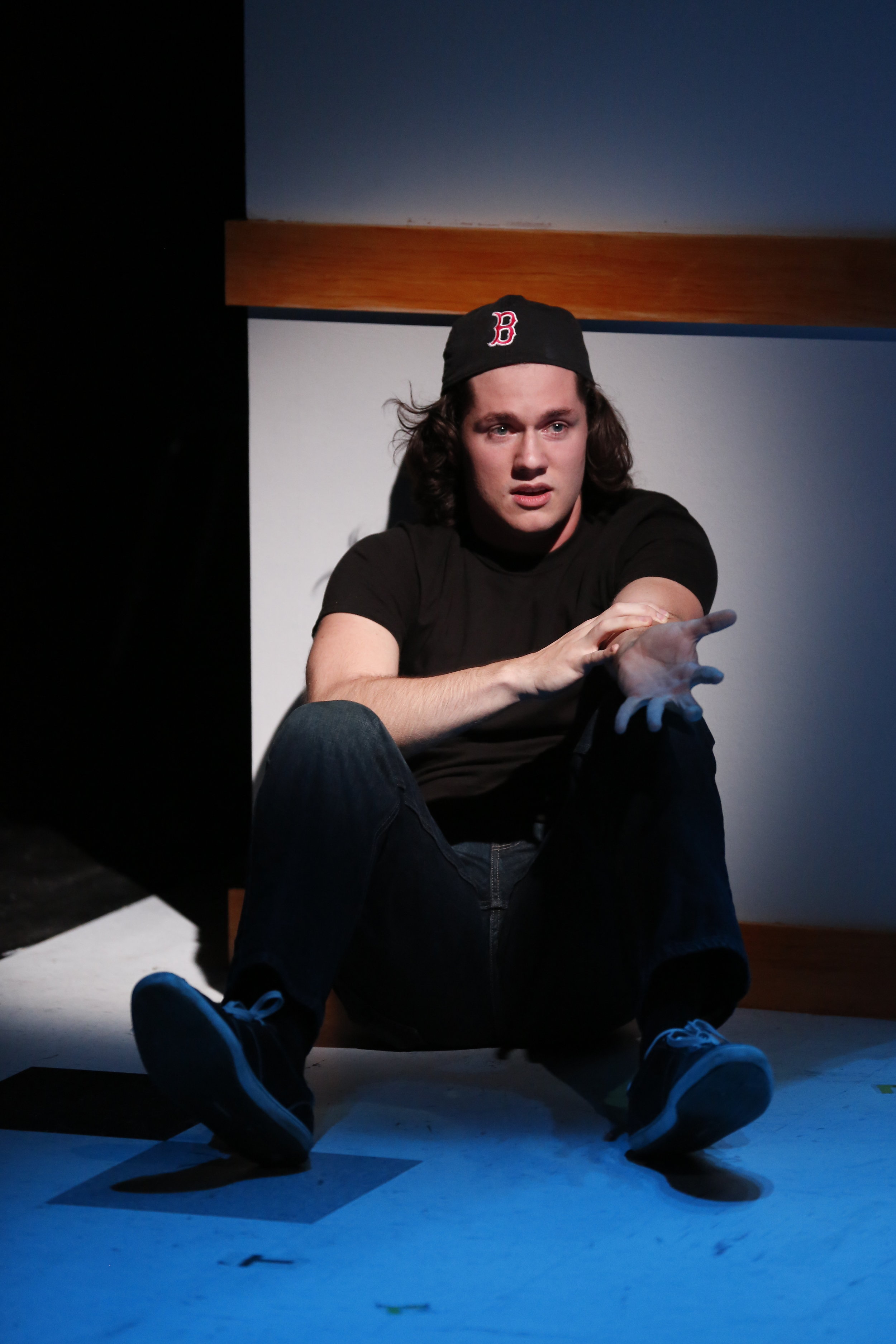

The Erlkings

The Erlkings (Die Erlkönige) explores the inner lives of Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, the perpetrators of the Columbine High School Massacre. The play uses real quotes from researched material left by the boys- journal writings, school assignments, chat room conversations, home videos - and combines it with original scenes, dramatizing the glimpses of recorded information that they left behind.The Erlkings (Die Erlkönige) posits that insight can be found into the violent American psyche that continues to rear its ugly head in our schools, through the dramatic exploration of the emotions and encounters experienced by the two boys.